The agricultural industry

is at the crossroads in terms of workforce capacity.

Agriculture has always been a complex business. In the 21st Century, however, the degree of complexity has intensified. Not only do farmers

and their advisers

need to contend with the usual production issues,

they also need to be increasingly self‐reliant in the marketing of their products, ensuring market

quality and supply.

There has always been a need to deal with climate

variability but predictions indicate that this variability will increase and there is increased

expectation for farmers

to manage the risk of drought. The compliance aspects

of the workplace continue to increase as occupational health and safety provisions apply together

with, inter alia, pesticide management, flock care and stewardship of GM crops. At the same time agriculture manages over 60% of the Australian landscape and thus assumes

the responsibility for native vegetation, landscape sustainability, biodiversity and the like. Technologies such as GPS, precision

agriculture and remote sensing are now having impact

and there is increasing expectation on agriculture to address

carbon emissions and play its part in the carbon economy.

Farmers need increased personal

capacity but thus will need greater

reliance on expert

advice from outside the farm. Research and development will continue

to be needed to develop

systems and technologies that allow productivity gains to maintain

farm profitability and address the needs and opportunities in food security nationally and globally. The industry, from the farm, the service

and post‐farm gate sectors

and in R&D, requires

a workforce which is highly educated,

highly skilled and with an image and reputation that is attractive to the best and brightest. As markets

become more discriminatory in respect

of quality and production practices, accreditation will become

increasingly important and the industry will need to have robust mechanisms in place to assure those markets.

Benchmarking education in agriculture

On any analysis, the educational standards of the agricultural industry

do not stand up well to scrutiny (Figure

1). Over the past quarter of a century the proportion of the Australian community with tertiary qualifications has increased from just below 10% of the workforce

to more than 25%.

In contrast, in the agricultural sector, only 4% were degree holders in 1984 and in 2009 that proportion has risen to only around 7%. The gap is widening, yet food production would seem to be an essential service industry where standards should be unquestionably high.

In contrast, in the agricultural sector, only 4% were degree holders in 1984 and in 2009 that proportion has risen to only around 7%. The gap is widening, yet food production would seem to be an essential service industry where standards should be unquestionably high.

Figure 1 Relative

proportions of the agricultural sector and the Australian community with tertiary qualifications, 1994‐2009 (Source:

Australian Bureau of Statistics)

The comparisons

are also stark

if the relative

proportions of the workforce

without post‐school qualifications are considered (Figure 2). Whereas the Australian community at large has reduced

the proportion

from 54% in 1984 to around 33% in 2009, the agricultural industry has achieved a reduction from 73% to only 58% in the same time – that gap also continues to widen.

Figure 2 Relative

proportions of the agricultural sector and the Australian community with no post‐school qualifications, 1984‐2009 (Source:

Australian Bureau of Statistics)

It is clear from these statistics that education of its workforce has not been a high priority for the agricultural industry.

Yet this became a concern

for the Heads of Agriculture schools

within universities where declining

enrolments were being experienced whilst

at the same time industry employers were complaining about the lack of graduates. In order

to address this issue in particular, the Australian Council

of Deans of Agriculture was formed in 2007. Further investigation by the ACDA revealed

the government policy

position at the time was that graduate

supply was plentiful but that job prospects were poor. This conflicted with the experience of the ACDA members

who embarked on a data gathering

exercise to clarify

the conflict. In this process

it was discovered that

graduate numbers

used by government included all environmental science and management graduates and that the job market

projections were based

on advertisements placed only in selected metropolitan newspapers.

Graduate supply in agriculture

Data were collected from all universities with undergraduate coursesin agriculture and in related areas. Such data were collected

from 2001 until the present

to establish trend lines. Figure 3 shows the graduate completions in agriculture courses

over time and Figure 4 shows the data for agriculture and related

courses for the same period.

Where available, comparisons are made with the 1980s using data derived from the “McColl

Report” (McColl

et al., 1991). Completions in the latter case were estimated in proportion to enrolments in the various levels of qualifications and so there are likely to be small errors in the absolute numbers used, although comparisons are not likely to be significantly compromised.

In the late 1980s there was a marked increase

in the number of graduates

with agriculture degrees, due largely

to the conversion from diploma

qualifications to degrees in the Colleges

of Advanced Education (CAE) sector.

Diploma qualifications have largely

disappeared from tertiary

education institutions since then. There was also a small component

of 2‐year associate

degrees at that time and they have also become virtually extinct. Together

degrees and associate degrees

in agriculture delivered to industry around

800 graduates in the late 1980s. In the 21st Century, numbers had declined to around 500 in 2001 and that decline has continued

such that only 300 degree graduates in agriculture entered

the workforce at the end of 2010. There has been a 40% decline

in last 10 years.

Figure 3 Graduate

completions in 3 and 4 year agriculture courses from Australian universities for the period 2001‐2009 inclusive and estimated

from McColl report

for years 1986‐1989 including

2 year associate

degrees

The agricultural

industry, however,

also receives value

from graduates in related

degrees such as horticulture, agribusiness, animal science and agricultural economics (Figure4). Whereas

the total graduation cohort

from agriculture and agricultural‐related degrees was around 1000 per year in the early part of the recent decade, the number has declined

to around 800 in 2010, ie a 20% decline.

However it should be noted that a sizeable

proportion of these are animal science graduates, only

some of whom (probably

fewer than half)are interested in livestock production with the remainder focused on wildlife

and companion animals.

The total available to the agricultural workforce then is closer to 700. Whereas animal science

degrees were not available for the period studied in the McColl Report,

there has been a proliferation of university courses in animal science

in more recent times to capitalise on high student

demand and, in many cases, to capitalise on the overflow of high quality students unsuccessful in their attempts to gain entry into Veterinary Science.

Figure 4 Graduate

completions in 3 and 4 year courses in agricultural and related

areas from Australian universities for the period 2001‐2009 inclusive.

The data in horticulture reveal

a substantial decline

as well. This sector during the 1980s was characterised by a relatively small cohort of degree graduates and a high associate

degree activity.

These consolidated into degrees and at the turn of the century

there were about 120 graduates

per year. This reflected the buoyant

position of viticulture at that time but there

has been a decline in the number

of providers related to the downturn

in the grape

industry. These numbers

also include graduates in the amenity

horticulture field as well as the very few in production horticulture. Thus the production horticulture industry will be dependant on agriculture graduates

for its professional workforce, as before, and so will have to compete with the rest of the agricultural industry for employees. Several

universities in recent

times have deleted

horticulture degrees

from their profile.

Figure 5 Graduate

completions in horticulture/viticulture from Australian universities for the period 2001‐2009 and the degree completions estimated from the McColl

report for the period 1986‐1989 including 2 year associate degrees

The discipline of agricultural economics did not have associate

degrees in the 1980s and so comparisons are straight forward. Completions back then were around 80 to 90 per year but in the

recent decade

is now around 50 per year except

for a peak in 2006. Only 3 universities provide graduates in this area with the University of Sydney

providing the vast majority. Student demand suggests that there will be no new providers in the market any time soon.

Figure 6 Graduate

degree completions in agricultural economics for the period

2001‐2009 inclusive together

with estimates of degree

completions from the McColl Report

for 1986‐1989

In agribusiness/agicultural commerce, the main qualification in the 1980s was the associate

degree being around 80% of the market.

Together with degrees, these awards provided

more than 200 graduates per year. In the evolution to degree‐only awards in the last two decades

there has been considerable fluctuation around

150 graduates per year declining

to fewer than 100 in 2010.

Figure 7 Graduate degree

completions in agribusiness for the period 2001‐2009 inclusive

together with estimates

of degree completions from the McColl

Report for 1986‐1989 including

2 year associate degrees

Workforce demand

The job market

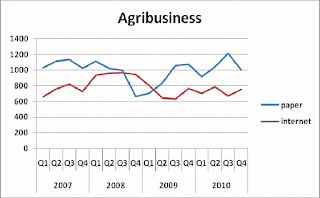

in agriculture is based on the monitoring of job advertisements in state rural and metropolitan newspapers and on the internet over a four year period, 2007‐2010, presented quarterly. The detailed

methodology has been provided

in an earlier paper on this topic (Pratley

and Hay, 2010). It is recognised that there is the likelihood of an advertisement being placed both in print and on the web and subsampling suggests

that this is of the order

of 20% for agribusiness and

conclusions have been adjusted

accordingly. It is also recognised that there is the potential for “churn” where one advertisement is generated by the filling

of another vacancy

but this is balanced by jobs in local media,

by word of mouth and direct targeting of employees, none of which is considered here. There is thus no adjustment for “churn”.

Data are provided

for agribusiness and production for the four years

of study (Figure

8). Total job numbers are consistently in aggregate around 4000,

or 3600 per quarter after adjustment for advertising overlap

in agribusiness. Despite

the drought, which was very severe in 2008 and 2009, the number of jobs was not affected

to a large extent although

a rise is evident towards

the end of 2010 as confidence returned

with the breaking

of the drought

in eastern Australia.

Figure 8 Number of job advertisements per quarter in agribusiness and in agricultural production for the period 2007‐2010 inclusive.

For 2009 and 2010, production advertisements have been categorised into management and non‐ management (Figure 9) to enable a better understanding of the required workforce. In the production sector, there was a consistent demand for some 2000 non‐management employees per quarter

and at least 300 managers per quarter. Also evident

in the data is the differing

role played by the internet in advertising jobs. In agribusiness the ratio

of paper to internet

advertising is around 5:4 whereas for on‐farm management roles the ratio is 3:1 and for non‐management jobs it is more than 10:1.

(a)

Figure 9 Influence of the internet in job advertisements by quarter

in (a) agribusiness in 2007‐ 2010, (b) management in production in 2009‐2010 and (c) production non‐management in 2009‐10

Figure 10 shows the categories of jobs per quarter for the agribusiness sector.

Particularly strong were the livestock and cropping categories but there were at least 100 advertisements per quarter for all categories.

Figure 10 Number of job advertisements per quarter in various

sectors of agribusiness for the period 2007‐2010 inclusive

The relative proportion of jobs advertised in the metropolitan press is particularly low when compared with those in rural

papers. The exceptions are in Tasmania and Western Australia. In the states of NSW, Victoria and Queensland in particular, metropolitan newspapers have very little influence on the job market in agriculture.

Figure 11 Relative

number of job advertisements in metropolitan and rural newspapers in each state for the period 2007‐2010 inclusive

Discussion

Regardless of the needs of the industry

the level of educational attainment in the industry is unacceptable in a community

which has education as a high priority.

It is clear that there

has been much complacency towards

the improvement of skills and knowledge of its workforce

at a time when the rest of the community

has embraced the opportunities and moved well ahead. It is not surprising therefore that the image of the industry

is not seen as progressive and the younger generations have not seen the opportunities for careers

in agriculture that are seen in other industries. The reality however

is that the greater expectations placed on producers and the associated services

requires a highly educated and skilled

workforce and there are opportunities for exciting and rewarding careers.

The evidence is provided that the industry

has a strong employment market.

The data presented in this paper show that there is a job market

of about 1600 per quarter

in agribusiness. If it is assumed

that 70% have a need or desire

for graduates to fill those positions then there is a demand for around

4500 graduates per year. To this should be added the 1200 or so production management positions annually. Whilst the percentages used could be debated,

what is clear is that the number is sizeable.

The universities are nowhere near satisfying the current market.

The data show that only around 300 agricultural graduates

per year are now produced. This number grows to over 700 per year when related courses

are considered. These numbers

assume that there is no leakage of these graduates out of agriculture – this leakage can be significant. At best therefore

the universities are producing only 700 or so graduates for a job market of more than 4000. Further, the universities would need to produce

about 2300 graduates just to maintain the current

(7‐8%) graduate level

of education

qualifications (Pratley

and Copeland 2008) and that is nowhere near being achieved.

Industry responds to this dilemma

in many ways – the workload

builds on existing

staff; staff are “stolen” from competitors but the expertise

base is not increased; and less qualified

people are employed thereby

reducing the quality

of service to clients

and for the business. Anecdotal evidence from industry is that qualified

people are leaving the industry due to the work demands being placed upon them,

thereby exacerbating the problem.

A consequence of the decline

in student numbers

is the inevitable decline in the number of providers. The McColl

Report in 1991 recommended that there be a consolidation of providers, on the pretext that the resultant providers would be more multidisciplinary and stronger

than many of the earlier era. Whilst the rationalisation has occurred and almost all are part of multi‐disciplinary organisations, the low student

numbers have not provided

the strength in many campuses that would have been expected. Thus providers of undergraduate agriculture courses have almost halved in number (Figure

12) fulfilling the recommendations of McColl

and colleagues. Of greatest

concern is the decline by about

two thirds in country

campuses offering

agriculture. Thus access by rural students to agriculture has become

highly limited yet it is rural‐based graduate

jobs which are the most difficult

for employers to fill. Every state capital

city except Brisbane currently

retains at least one campus

where undergraduate agriculture is offered.

Figure 12 University campuses offering

an undergraduate agriculture degree, 1989 and 2011

By any measure, the agricultural industry faces immense

challenges in capacity.

Prospective students and their mentors do not see agriculture as a potential career

path. Thus students

are not entering relevant university courses

in sufficient numbers

even to maintain

the current levels

of workforce education. The issue is not that there are no exciting

and rewarding careers

in agriculture – it is that the emerging workforce

generation does not perceive those opportunities in agriculture and is thus attracted to the more positive

images portrayed in other employment settings.

If the trend in student enrolments continues we can expect to have further

universities dispense with agriculture courses.

It is unlikely, once relinquished, that any institution would re‐establish such a course.

The industry as a whole seems reluctant

to embrace education

as an essential plank of its future sustainability and seems unwilling

to work together

to promote both a positive

image for the industry

and worthwhile careers

for prospective participants. The industry as a whole

seems to be

reluctant to put pressure on the political

system to lead the image repositioning and career promotion. There are now sufficient data available to have established that the capacity

challenge is real. The challenge

will intensify unless there is concerted effort for change.

Acknowledgements

The personnel at Rimfire

Resources are gratefully acknowledged for their contribution to the collation of all the advertisement data used in this paper.

Reference

McColl, JC, Robson, AD and Chudleigh, JW (1991)

Review of Agricultural and Related

Education. Volumes 1 and 2. Department of Employment, Education and Training

and Department of Primary Industries and Energy (AGPS, Canberra)

Pratley, J and Copeland, L (2008)Graduate completions in agriculture and related degrees

from Australian universities, 2001–2006. Farm Policy Journal

Vol. 5 No. 3, 1‐10

Pratley, J and Hay, M (2010) The job market in agriculture in Australia. Occasional Paper 10‐01, Australian Farm Institute, pp1‐14

Post a Comment